Helen Roche discusses the phenomenon of student exchanges between the elite schools of Nazi Germany, Britain and the U.S. during the 1930s

In spring 1936, teenage schoolboy and later war-hero Dick Hargreaves was given the chance to go on an all-expenses-paid exchange trip to Germany. But this was no ordinary school exchange – Dick’s destination was Oranienstein, one of a system of newly founded elite boarding-schools known as National Political Education Institutes (Napolas for short).

These Nazi colleges were explicitly modelled on an amalgam of the British public schools, the Prussian cadet-corps, and the harsh educational practices of ancient Sparta. The schools educated boys from the age of ten upwards, in order to train them as future leaders of the Third Reich. By taking part in the exchange, Dick Hargreaves and his ten companions from Dauntsey’s School in Wiltshire would soon be exposed to the Napolas’ ‘total’ programme of education, indoctrination, and National Socialist propaganda.

Dick’s initial impressions, recorded in his diary at the time, are overwhelmingly favourable; the school is described as ‘a damn good place… a huge castle, done up modern and very posh – armchairs, super labs, stables, …school bicycles and heaven [knows] what!’.

According to the diary, everyone is ‘extraordinarily decent’, and the boys’ Nazi uniforms are ‘very smart indeed – light khaki corduroy breeches, black riding boots, khaki coat, red arm band with swastika, brown coat lapels, blue shoulder straps and a dagger thing.’

Most interesting, though, is Dick’s dispassionate observation of the Nazi Mayday celebrations in the neighbouring town of Diez:

Thursday [30th April]

...In the evening we went down with our Kameraden to Diez and watched the Maypole being hoisted and folk dances by the Hitler Jugend and heard speeches by some of the big bugs of the town. There was also community singing in which we all took part. There was a good bit of “Heiling” which we also did because we were in a huge crowd. It was a magnificent scene – the old castle towering above the market place in which were thousands of enthusiastic peasants lit by torch and candle light…

Friday !! [1st May]

Frühlingsfest! We had to get up at 6 o’clock to salute the flag and parade. After a hasty breakfast we paraded at 7.15 and marched down to Diez… the school had to line two sides of the square. At 8.30 when all the Hitler [Youth] had arrived and the Motor School we had to stand still for 1¼ hours listening to Hitler speaking on the wireless!! After this ordeal was over, it was just about 10 and we marched back to the Schloss again – for the rest of the morning we sat and recovered. After the usual lunch we marched down to parade in Diez again. W[hen] all the citizens, the Motor School and the labour camp people had marched into the[ir] respective places in the square we had to listen to Hitler speaking for 1¾.

He worked himself into such a frenzy and was able to move the crowd so tremendously that we saw three people faint. Not from fatigue or crush but just by his amazing oratory powers. Then after Hitler had been “Heiled” off the earth Goering spoke for ½ hour! Then all the military and otherwise people paraded all the streets of Diez, then the School marched back to Oranienstein…

Here, the way in which foreign observers could easily be swept up in the fervour of ‘heiling’ and Hitlerism around them is made poignantly clear – although the interminable speeches by Hitler and his henchmen seem to have palled soon enough.

During the 1930s, hundreds of pupils took part in these exchanges and sporting tournaments with the Napolas. Just to take one example, between 1935 and 1938, Napola Oranienstein took part in exchanges with Westminster, St. Paul’s, Tonbridge School, Dauntsey’s, and Bingley School in Yorkshire, entertained headmasters and exchange teachers from Shrewsbury School, Dauntsey’s, and Bolton School, and was also involved in sports tournaments with Eton, Harrow, Westminster, Winchester, Shrewsbury, Bradfield, and Bryanston.

What’s more, the Napolas also took part in exchange programmes with several U.S. academies under the aegis of the International Schoolboy Fellowship, including Tabor Academy, St. Andrew’s Delaware, and Phillips Academy Andover.

Ultimately, the Nazi regime wanted the German boys and staff to act as the Third Reich’s ‘cultural ambassadors’, gaining sympathy for Hitler’s policies, and spreading pro-Nazi propaganda. Many British headmasters were persuaded of the wisdom of these exchanges – for instance, E.K. Milliken, head of Lancing House Prep School in Lowestoft, was so enthused by his experiences with the Napola in Naumburg that he even wrote an article exhorting all members of the Association of Prep Schools to welcome the Napolas with open arms.

Even those who were less easily convinced, such as headmaster A.B. Sackett of Kingswood School in Bath, hoped that the programme could provide ‘a chance to influence the sons of senior Nazis by discussion and friendship’. The American reaction seems to have followed a similar pattern, with the headmaster of Tabor Academy, Walter Huston Lillard, still trying to persuade American schools to continue with the programme even after Kristallnacht.

Overall, both the British and American participants in the Napola exchange programme appear to have been ready to give the Nazis the benefit of the doubt, at least at first. While they may not have been convinced by the Third Reich’s aims and ideals, they continued to hope that their national differences could be cast aside in the name of international cooperation, until Nazi belligerence reached its fatal climax.

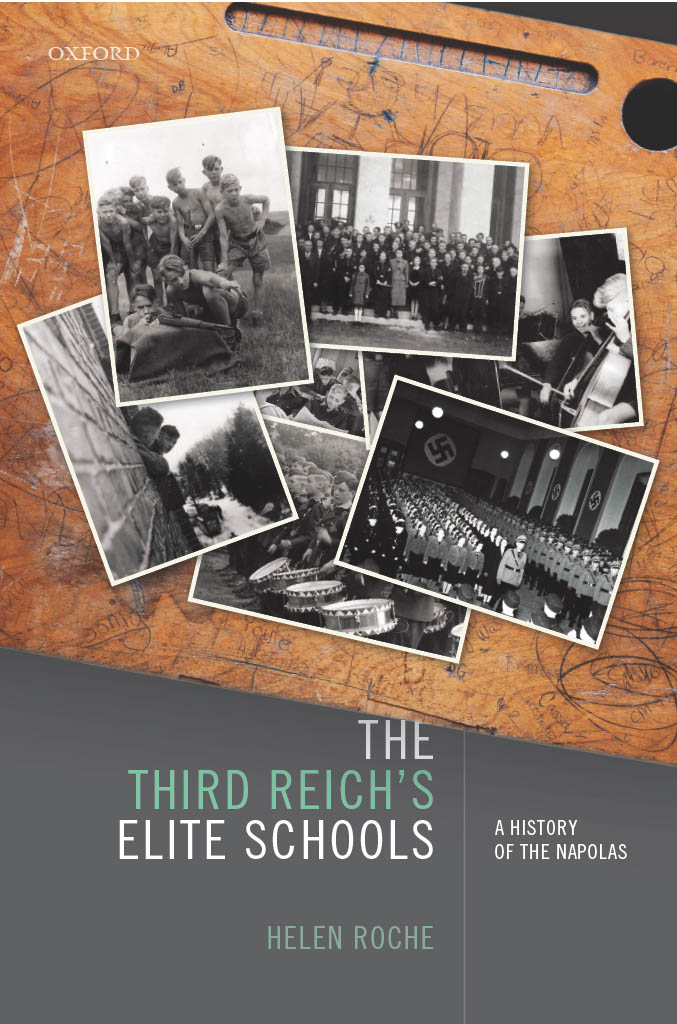

Dr Helen Roche is Associate Professor in Modern European Cultural History at the University of Durham. Her second book, The Third Reich’s Elite Schools: A History of the Napolas, has recently been published by Oxford University Press.

Helen previously held a Research Fellowship at UCL’s Institute of Advanced Studies.

Featured image: Football match between pupils at NPEA Ballenstedt and an un-named English public school, April 1937

Note: The views expressed in this post are those of the author, and not of the UCL European Institute, nor of UCL.

Leave a comment