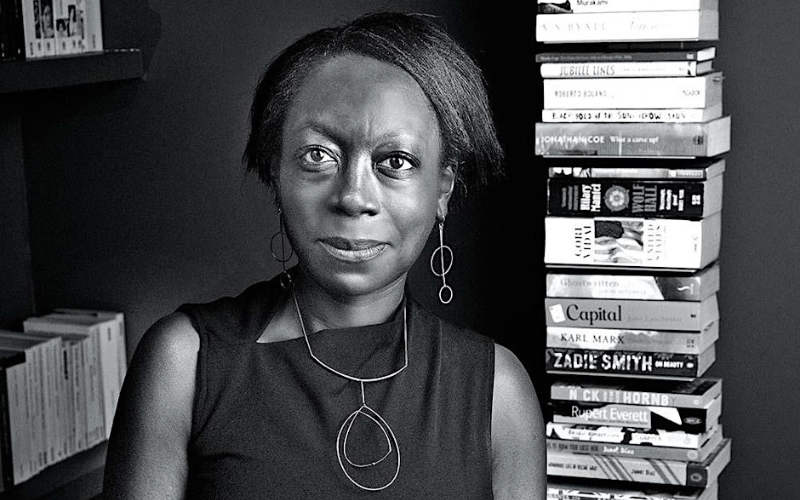

European Institute Student Ambassador Alexander Anderson interviews Diamond Ashiagbor about pushing boundaries in her field by placing race and colonialism at the centre of labour law research. As a Professor of Law at the University of Kent and Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the UCL Institute of Advanced Studies, her work examines the intersections of EU law, labour law, and the legacies of colonialism. He spoke to her about her groundbreaking research and how these historical foundations continue to shape labour markets and social policies today.

The EU, Decolonisation, and Social Policy

Professor Ashiagbor’s academic journey has been shaped by her interest in the EU’s social dimensions and labour law. Reflecting on the origins of European integration, she highlighted how the Treaty of Rome, often seen as a cornerstone of economic unity, also contained significant provisions for overseas territories. These sections, she noted, are frequently overlooked but are crucial for understanding the colonial entanglements of the European project.

She pointed out that in the 1950s and 60s, European integration coincided with the wave of decolonisation. “Four of the six founding states of the EEC were colonial powers,” she remarked, “and France is particularly notable, as its overseas departments like Algeria were part of the single market for goods, services, and workers.” This colonial backdrop, she argued, casts the EU itself as a potential neocolonial project, echoing critiques made by figures like Kwame Nkrumah in the 1960s.

Even today, she explained, colonial histories influence the EU’s social policies. Labour migration into Europe often reflects these legacies, with former colonies supplying significant numbers of workers to countries like France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The demographics of European cities, she said, are a visible testament to these historical relationships.

Labour Law and Historical Continuities

Ashiagbor’s research also draws a through line from historical systems of unfree labour to modern employment structures. She described how colonial economies transitioned from slavery to indentured labour, with the British Empire moving workers from India and China to Caribbean plantation economies after the abolition of slavery. These shifts, she argued, were legally enforced, with criminal law used to punish workers who broke contracts or fled employment.

“Modern labour laws no longer rely on criminal sanctions,” she explained, “but the legacy of these systems persists in today’s employment structures.” She used the example of the UK’s healthcare system to illustrate this point. Core workers like doctors and midwives typically have stronger employment protections, while peripheral workers, such as cleaners and porters—often racialised migrants—are employed precariously through outsourcing agencies.

She emphasised that these disparities are not coincidental. They reflect a continuation of historical inequalities, where racial and ethnic hierarchies shape access to stable, well-paid work.

Rethinking Labour Law through Race and Colonialism

One of the central arguments in Ashiagbor’s research is that labour law’s existing frameworks regularly fail to address structural inequalities. “Labour law tends to focus on individual relationships, such as an employer treating an employee unfairly,” she noted. While such protections are important, they do not tackle deeper systemic issues rooted in colonial histories.

She argued that the dominant form of employment—governed by contracts—has racialised foundations. Historically, unfree forms of labour like slavery and indenture operated outside such frameworks, but their legacies influence how modern labour markets are stratified. Racialised workers, particularly migrants, are often relegated to precarious, low-paid roles, perpetuating patterns of marginalisation.

When asked about migrants from Eastern Europe, such as Polish workers in the UK, Ashiagbor acknowledged that racialisation extends beyond skin colour to include xenophobia and ethnic differentiation. She highlighted how migration policies, influenced by geopolitical contexts like EU membership, have further stratified labour markets.

Towards a More Inclusive Labour Law

Through her research project ‘Reconceptualising Labour Law: Race, Legal Form and the Legacies of Colonialism’, Ashiagbor challenges the field to reckon with these historical and structural inequalities. By centring race and colonialism, she hopes to develop frameworks that address not only overt discrimination, but also the deeper legacies shaping modern employment.

Her work offers a vital lens for understanding how labour markets function and who they serve. As she concluded in our interview, “Race is embedded in the legal form governing modern work, and recognising this is essential for building a fairer, more inclusive system.”

Professor Ashiagbor’s research invites us to confront uncomfortable truths about the systems we rely on and to imagine labour law that not only protects workers but also dismantles the inequalities of the past.

Alexander Anderson is a UCL European Institute Student Ambassador and in his second year studying for a Bachelor’s degree in French and Spanish. He has an avid interest in student journalism, content creation, and outreach to promote European studies.

Featured image: Picture of Diamond Ashiagbor via the University of Kent

Note: The views expressed in this post are those of the author, and not of the UCL European Institute, nor of UCL.

Leave a comment