This article forms part of the report The Centre’s Last Chance? Lessons from the 2025 German Elections from the UCL Policy Lab and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES). Read the full report here for more analysis on results and the lessons that can be learned for other centre-left and centre-right parties in Europe, including Britain.

To be conservative, according to this most British of institutions, the Oxford English Dictionary, is to favour preserving, or keeping intact, an existing structure or system: to be averse to fundamental change.

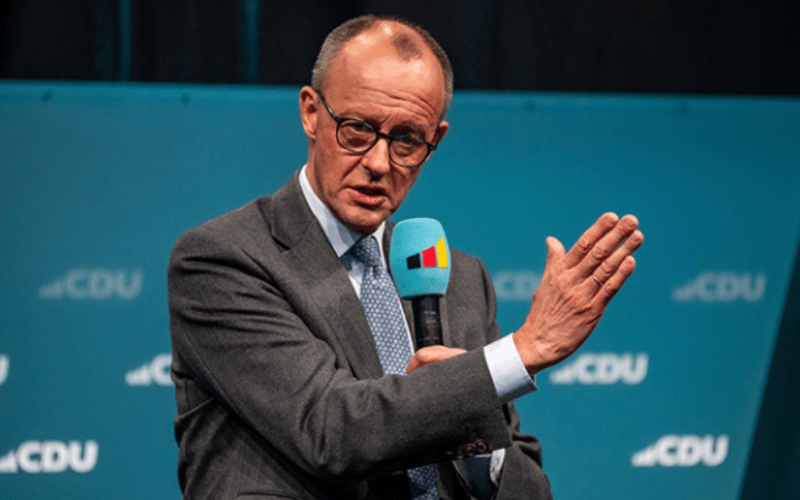

The likely next German Chancellor, leader of the German Christian Democratic Union Friedrich Merz, has a particularly conservative reputation. Distinctly to the political right of his long-time rival, former Chancellor Angela Merkel, he is also seen as a social conservative, be it in the area of family policy and bioethics, or in discussions about German Leitkultur, its supposed core national values.

And yet, in the space of just over a month, Merz has protagonised two of the most significant political volte-faces in the 80 years since the end of World War II. Immediately pre-election, he sponsored a bill to tighten immigration policy that breached the firewall – a formerly unassailable normative position in German politics to not work with, or propose any parliamentary motions that rely on the votes of, the extreme right. It did not stand him in good stead.

Immediately post-election, then, he went on to break with another, previously indisputable, tenet of the German political centre-right. Asserting, shortly after the polls closed, that the United States no longer “care much about the fate of Europe”, he called for immediate action to strengthen Europe “so that we achieve independence from the US”. A day later, he warned: “This is really five minutes to midnight for Europe.”

These remarks found rather more approval, both domestically and Europe-wide. Yet they represent an unprecedented about-turn by one of the most explicitly Atlanticist German politicians of many years, a former chairman of the influential Atlantik-Brücke, which has advocated for close economic, financial, educational and military partnership between Western Europe and the US since the early 1950s.

“I never thought I would say this”, Merz admitted. And not just because of personal convictions. Atlanticism has been in the DNA of German conservative politics since the early post-war days. The first Federal Chancellor, Christian Democrat Konrad Adenauer, recognised the US as ‘ultimate arbiter’ in his efforts to integrate the FRG as a newly sovereign and equal member in Western Europe and the Atlantic Alliance. Indeed, Western European Christian Democrats, strongly supported by close transatlantic networks, were the architects of European integration in the early days. In the face of Soviet threats, the US pushed for German rearmament; both advocated for the (ultimately doomed) European Defence Community. It is only in the context of a security environment that is changing radically and at blistering pace, then, that Merz’ repositioning is even conceivable.

These stark geopolitical shifts give two new meanings to another most British concept: the “squeezed middle”. Domestically, first, centrist parties feel ever more pressured by the return of a nativist politics that is developing on both fringes of the political spectrum, if meeting on far-right grounds. Beyond the US, German just as much as the French presidential and indeed the latest European parliament elections are a case in point. It is entirely in the UK’s own interest to seek to counter the appeal of populist parties, which are so comfortable with promising easy answers to all difficult questions – at home and abroad. A scenario in which the AfD wins the next German elections, Le Pen becomes President of France, and Reform UK take over from the Conservatives, is a high-risk one for democratic Europe, the UK included.

Second, geopolitically, Europe is now increasingly hemmed in on (at least) two sides by globally dominant forces no longer favouring liberal democratic principles. The US, so invested once in European unity and capability to face off the Soviet Union, now identifies Europe as an ideological threat, while siding with Russia. J.D. Vance’s comments at the Munich Security Conference clearly articulated this seismic shift in both normative and geopolitical terms.

It shows that for all political ideologies, history can come calling. Long-held assumptions and long-standing alliances can morph as the international environment does. Merz, Atlanticist parexcellence, is now turning away from the US and toward a new European security architecture – the ‘strategic autonomy’ long touted by French President Macron. Words might even be followed by – relatively – swift action, considering the usually slow pace of German politics. It is the one policy area in which Merz’ likely coalition partners, the SPD, is most aligned; former defence minister Boris Pistorius (SPD), Germany’s most popular politician, could return to his role.

This will have an impact on European collaboration, not least in the security and defence space. In addition to a likely revived Franco-German relationship, and even though not much love is lost between Merz and the European Commission president, his party-political colleague and long-time Merkel ally Ursula von der Leyen, their position on the EU’s ability to pursue its strategic interests globally may well align more closely now.

It will therefore be important for the UK to monitor the extent to which former MEP Merz is willing or able to take a more prominent leadership role in Europe than his predecessor – either way, the UK will feel the impact. But, with the very existence of NATO now being called into doubt, Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer will face difficult strategic choices about how he sees European-wide multilateral collaboration, including and particularly in security and defence matters, develop.

So far, he has been able to win over governments on both sides of the Atlantic.

Last October, the UK and Germany signed a landmark defence and security agreement. In early February 2025, Starmer discussed defence with EU heads of government over dinner in Brussels, the first British PM to do so since the UK left the bloc. More recently, European leaders made the return journey to discuss defence in London, ahead of a special European Council Meeting on the subject. It was a dramatic show of force in support of Ukraine, after President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s disastrous meeting in the White House – and one that continues. As recently as 15 March, Starmer hosted a Ukraine-focused call with counterparts from across Europe, EU Commission and Council, as well as the NATO Secretary General, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Yet Starmer is unlikely ever to deploy such stark words as Merz. The government continues to engage closely with the US, not least over the proposed ceasefire deal with Russia. Indeed, the diplomatic overtures on display at his first visit to the White House, and his liaison since, currently speak a diametrically opposed language – offers of a second state visit included.

The question will be to what extent this, literally pivotal, role will be open to Starmer as a strategic option in the long term, and not only due to the demonstrated fickleness of Trump’s trade and foreign policy preferences. If this is indeed now the beginning of a Zeitenwende, in which the liberal post-war order is being called into question, the government will have to confront increasingly fundamental political and normative choices. One conservative tenet after all is likely to guide political leaders on both sides of the Channel – the ambition to preserve or keep intact Europe, and its constitutional democracies.

Dr Uta Staiger is Associate Professor of European Studies and Director of the UCL European Institute. Since 2010, she has led the Institute in its mission to develop and support UCL research and teaching activities on Europe across faculties, advise UCL leadership on European matters, and maximise the reach and impact of UCL expertise beyond the university. In 2017, she was appointed as Pro-Vice-Provost (Europe), a strategic position shaping UCL’s engagement with European higher education partners and policy. In this role, she contributed to UCL’s Brexit mitigation planning and co-convened the university’s steering group on the research-based response to Brexit. She also worked on UCL’s institutional responses to the Russia-Ukraine war. Uta is now UCL’s Global Strategic Academic Advisor on Europe, working with the Vice-Provost for Research, Innovation and Global Engagement.

Note: The views expressed in this post are those of the author, and not of the UCL European Institute, nor of UCL.

Leave a comment